On Fair Governance and Evaluation — An interview with Katarina Pavić

Katarina Pavić is a cultural worker and activist, who worked in the independent cultural scene in Croatia and the wider region of former Yugoslavia since 2005. Her work has combined advocacy and research at the intersection of civil society development, activism, and cultural critique. She has been the facilitator of the fair governance models trajectory of RESHAPE, which describes it as a ‘reflection-oriented process, where its focus – governance of artistic and cultural institutions and collectives – functions simultaneously as a form of critique and an open invitation to imagine and practice a different way of being-in-common’. In this conversation, she spoke from London where she pursued her MA in culture industry and to which she has just moved back.

[Lina Attalah] How was the question of fair governance first introduced and debated throughout the various workshops and the process that followed? I saw questions about the future of governance, and whether fair governance can become a form of emancipation. What were these questions about and what were other questions?

[Katarina Pavić] The workshops within this trajectory had eight different cultural workers and artists scattered throughout Europe and the southern Mediterranean. Each has their personal path as individuals embedded in their own context. So the main question was pertinent to the group in the widest possible context. Governance is a form of being together actively, a form of organising our work. Many can benefit from being together and this was the starting point for many conversations as a group. Very early in the process the group desired to treat governance not just topically but also performatively, as an experiment, looking into the different ways how governance could be challenged and practiced within the context of RESHAPE itself.

I participated in the group and was not just there in a neutral position or a technical role of facilitator. I actively took part in producing with one of the two subgroups that were formed from the trajectory. The group had decided from the beginning to think through principles of fair governance, and hence to abolish roles like that of the facilitator as a central role, as a secretary general to the group, dictating its tempo. We agreed that I’d be a person who had coordination tasks but who was also an equal participant. I had a voice content-wise, but no higher authority. That was important for the context of RESHAPE overall, in order to practice the notion of fair governance within it as an experiment.

The contexts we came from and our different personalities led us to these questions: How to distribute assets, money, and power? How to distribute these to the ones disenfranchised in the world and also understand the disenfranchised as nature, as animals or other inanimate objects.

I come from the Balkans and I moved recently, currently living through my own diaspora experience in Great Britain. Once you move, be it temporary or permanently, you’re always split between places, memories, and personal ideas and prejudices about how a certain place functions. Accordingly, we had a lot of challenges to surmount our differences and find the common denominator that connected our stories. Next is how to take that to the experimentation phase and what this means for RESHAPE and the wider community of artists and cultural workers.

[LA] There have been discussions of different forms of governance in your encounters such as questions of self-governance and participatory governance. What were some examples of alternative modalities of governance that were discussed?

[KP] There were various existing practices that inspired the group, such as holacracy, which is an advanced type of decentralised decision making, a type of subsidiarity where as many decisions as possible are taken locally to avoid centralisation of decision making. There were other examples too, such as Bhutan’s National Gross Happiness index and the work of numerous different collectives globally that have inspired our work.

What was really interesting is that we began to rethink who is allowed to be present at the table. Who is invited? Who is not invited? How do we detect these blind spots, these tropes of omission while having good intentions? And accordingly, who is allowed to speak? These are important questions in order to engage how the ones who are not there can become a voice, a legitimate part of decision making, and are not just being informed.

What is also important was to rethink our paradigms as a group, but also as the entire body of independent cultural actors. Our focus has been on how to secure the survival, this bare minimum of survival of the living, of the creatures, of freedom, of women, of speech, of justice. How to ensure this transition is solidary?

This made us realise that our ambition has been too big and our impact too small. We opted to asking how we can free ourselves from of the logic of capital and rationalisation and instead rethink how things should be done. It was important as a group to think in this way, so we would not be distracted from the topic of our work.

[LA] It seems you have inhabited the conditions of that which you were set on discussing and exploring, but also the question of barriers to entry in such projects seems to have been present in the other trajectories too.

I am interested to know how local experiences in Tangier and Sofia, where you held your first offline meetings with the group, informed the discussion. There was a plan, for example, in Sofia to present to the participants, the Reshapers, the case of a power plant turned into a cultural space, which sounded very interesting. How did this site specificity inform some of your conversations?

[KP] Local contexts have been extremely important. If there was anything to criticise, it would be that there wasn’t enough time. Three days isn’t a lot of time, especially when you are trying to programme the days in order to create a balance between group work and getting to know local actors.

Through these local contexts, we witnessed the resilience and generosity of our host communities, specifically Think Tangiers and Tabadoul, the organisations that hosted us. This was shown to us in our meeting in Tangier. People there did great work showing us urban realities of local development. Tangier is radically changing through gentrification and massive investment from the Gulf region. You see these cinematic scenes of people living in slums with new developments evolving next door. What was moving for me was to see how local people are adjusting to these new situations and how they are doing a lot of hard work trying to emancipate themselves. We saw an immense amount of resilience.

In Sofia, Toplocentrala, the power plant we saw, was actually empowering the largest cultural centre in Sofia, and this is very symbolic. The plant hadn’t been in operation for a long time, as the power supply system to the city had changed, so the space was emptied out and left vacant. It had become a barren space that looked like a video game space. After many years of negotiations, the city put some resources and political will behind it and put out an architectural tender for this cultural centre to be constructed. The big question here is the governance of the space because what often happens is that ideas are hijacked by both the private sector and the government, who take over noble plans by independent players and then install their own people in decision-making positions. The project brought up not just the question of spatial reinvigoration but also of how the space belongs to the community and how does this community take decisions. These questions are still open. And as I come from the region and I am familiar with how politics work there, I know how endemic corruption is. In order for things to happen, you need to be connected to powerful structures on the national and city level.

[LA] During your meeting in Sofia, the group divided itself into two subgroups. Can you explain what they were?

[KP] Yes. It was a decision we took to try to organise ourselves in small units, not just for efficiency but also given the different interests within the group. There was a big difference of experience and interests within the group, and while some people were more interested in broad socio-political transformations, others were interested in more concrete issues that cultural workers experience and ways to tackle these issues. The two groups met and briefed each other, but they worked more or less separately.

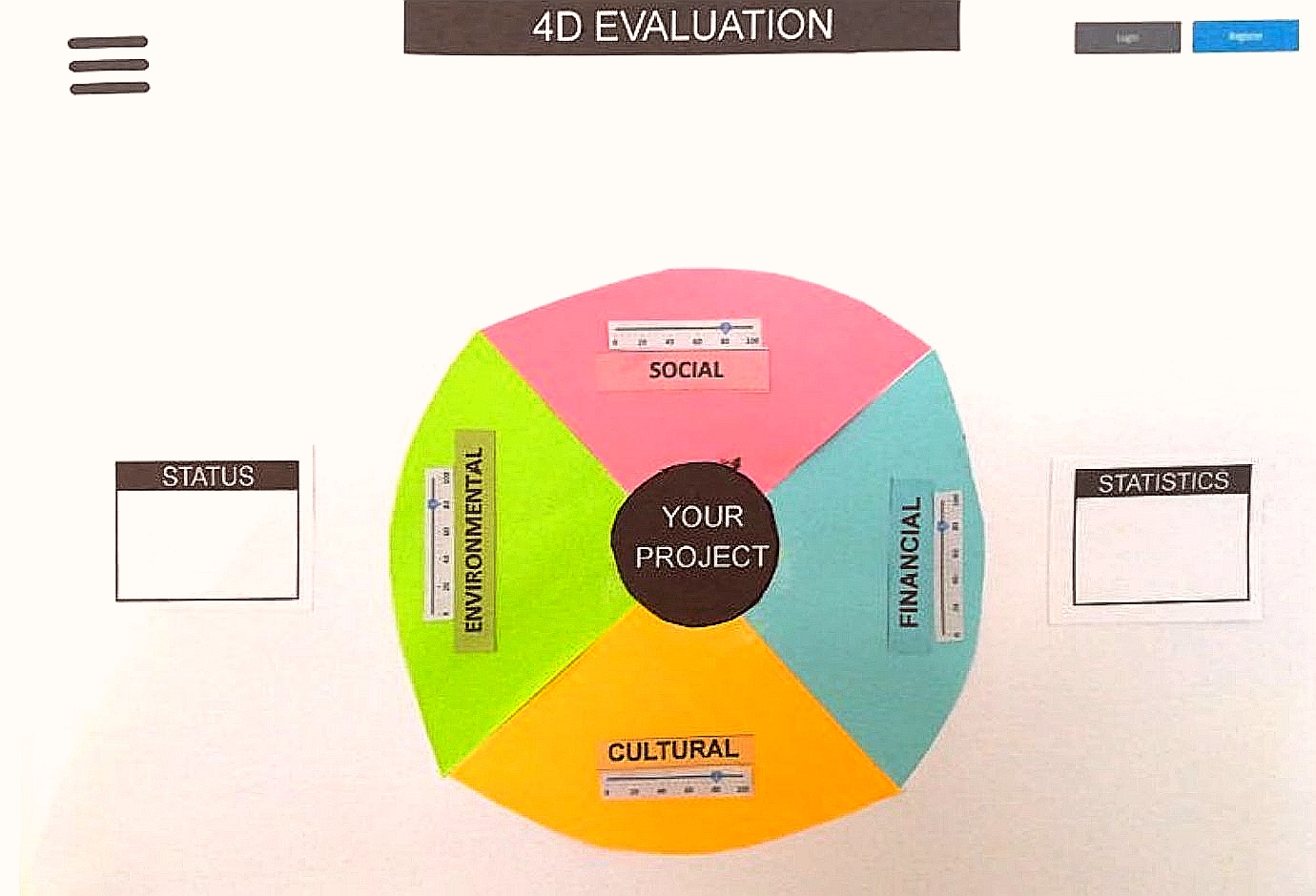

[LA] One of the groups worked on developing an evaluation prototype, which I would like to learn more about. But first, I would like to know your take on how you were encouraged to come up with a prototype as a concrete experiment as opposed to staying in a more conversational, dialectical, or discursive format.

[KP] I am not happy with the fact that we had to work towards a product but I guess the project was designed in line with a funding call, where you have to commit yourself to deliver something. There are usually doubts about the feasibility of projects where you say ‘we will come together and discuss the meaning of our work’ and that is sad because the biggest thing we need is this, without the expectations and the dictates of producing. However, we have tried to do our best to give some meaning to that prototype. So, while we were aware of the mercantile logic of producing, we were also aware that we wanted to do something that had value.

[LA] How did you tackle the question of evaluation as this interesting intervention in the context of fair governance and how did you go about creating a model for it?

[KP] We were thinking of avenues that inform good governance, and of questions of what we believe in, how we apply it in a governance model and how to measure all of that. When you toss these ideas together, you realise we are talking about evaluation. And when we are talking about evaluation, it is not just one, but many evaluations at the same time. It’s a problematic field because it is connected to money, and to external powers that dictate our work, but it is also our own incentive to constantly question what we are doing. Are we really understanding what we are doing? Are we perhaps missing a weaker signal? How are we engaging people we are working with within the collective, as well as our broader audience? For me, the evaluation project is a form of prismatic thinking. You have the abstract notion of governance, and then you look at it as if through a prism and cast out evaluation as something you do when you are running projects. This is how we tried to channel notions of governance without making completely technical interventions or too abstract ones.

[LA] How did you engage with this issue of evaluation as a tool of true and genuine disruption of working in a mechanical way to produce the same thing over and over? In other words, how did you enact the idea of evaluation as a form of habit breaking and rethinking practices?

[KP] We did some research and interviewed 14 people from different countries. It was important for us to find out how people deal with what’s imposed on them in terms of evaluation processes, what their organic practices of evaluation look like and how they cope with the differences between these two types.

What we found is that people always rely on close contact with each other, as they need a real and honest conversation. They need evaluation processes not just because these will improve their next projects but also because they help as a form of therapy, as you come to terms with things you have done wrong, but also things you did right. As humans, we tend to reference the positive quickly and then focus on the negative. But evaluation processes are there for us to see what we have done well and to analyse how we did it. It can be a visionary tool.

We had a concrete collaboration during the process with Faro, a collective of 14 cultural actors from Latin America and Spain who are mostly involved in theatre and performance. They have been developing advanced evaluation tools that are based on an examination of realities faced, with the intention to invent a new kind of metric not only made of quantification. It is still very empirical but also an attempt to work with real data in a human way. We based our work on the self-described futurist Brazilian philosopher, Lala Deheinzelin, who has a methodology connecting four different dimensions: culture, new economies of sharing and distributive mechanisms, environment, and social aspects. She argues that these four dimensions need to be examined in detail when you are embarking on an evaluation process. The collective took her theoretical work on what she calls ‘futuring’ and imagining better possible futures and used those four dimensions prismatically in order to invent a new methodology for evaluation.

One of our group members has been participating in this process and connected us to it. We stepped into their process and they were happy about having this other voice and this bigger geographical scope. Both groups were happy to find each other in this exchange and to see differences in thinking. For example, in Latin-American countries as well as the Global South in general, people tend to be more affective and less stiff. They turn emotions into something more pertinent. We have been dealing with how to inform our evaluation processes with affections, not to make them terribly emotional but to give emotions the legitimacy that they don’t have.

Together with Faro we want to simplify their methodology, to test it on RESHAPE and to see with the whole RESHAPE family if this tool is interesting for them.

[LA] What about the tarot cards that the second group developed as a game and a tool? I understand they have used cards of the Modern Witch Tarot Deck. What have they been trying to do?

[KP] The second group started up with a collaborative writing experiment about broad issues such as the injustices of capitalism, current prices, and so on. But they realised that it was a post-doc type of endeavour and that they didn’t have one question. Then we met and had a lot of exchanges, and ended up doing a collective tarot reading. We didn’t do a classic tarot card reading. We were rather pondering questions on decision making in organisations, financial challenges, dealing with injustice, and one card was dedicated to evaluation, which was being developed by the first group and that created a connection between the two groups.

The transnational/postnational trajectory within RESHAPE is also developing a set of cards and between us we will produce 22 cards altogether. This tool is a way of helping people come together, to discuss and evaluate using symbolic and visually enticing material.

[LA] As someone who has been both a facilitator and actively taking part, co-writing and co-designing one of the prototypes, what has been reshaped for you? Have you experienced any rerouting through this process?

[KP] Our experiences come in batches. We don’t experience things separately but rather in waves. I decided to change my life in my late thirties; I am from Zagreb, where I had a stable life and career and I just moved into a completely unstable life in London, which is a difficult place especially in terms of finances. Yet I made the deliberate choice of leaving and opening myself to different realities. RESHAPE came into this process to expand my view on how complex the world is. It has given me more understanding of difference. For some of us who have been part of this experiment, working as an artist or as a cultural worker has been extremely precarious. RESHAPE has given us a platform where we didn’t have to be too obsessed with the outcomes. We gained a lot more opportunity by just being together.

This text is licenced under the Creative Commons license Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International.