The Home, the Suitcase, and the Social Fabric — An interview with Pedro Costa

Pedro Costa is professor at the Department of Political Economy at the ISCTE – Instituto Universitário de Lisboa and director of DINAMIA’CET-iscte (Research Center on Socioeconomic Change and Territory). An economist with a research specialization in urban and regional planning, Costa works on areas of territorial development and cultural economics. In the context of RESHAPE, he was the facilitator of the trajectory Value of Art in the Social Fabric, where the question of how to better understand the impact, tangible and intangible, of artists and their work on the local context was raised. In this conversation, we explore some of the processes and outputs of this trajectory.

[Lina Attalah] Your trajectory is one that is placing art in the social context it belongs to, and I was wondering what the entry points and the theoretical underpinnings were through which you started your conversation with the Reshapers? For example, there is the common dialectic of producing art for art’s sake versus producing socially-responsible art. Was this, for example, a dialectic that featured in your early conversations?

[Pedro Costa] In the first meetings we had, both the plenary meeting and the one for our trajectory in Prague later, participants quickly wanted to go deep into the subject without discussing these issues too much. There was some discussion of art for art’s sake, socially responsible art, ecological responsibility, and so on, but only briefly. It was not what I had expected, as I come from academia and I thought people would be interested in such conceptual terms as the idea of impact and how we can measure impact in real life and not just in macroeconomic or quantitative terms.

Some of the Reshapers were already working on these issues so for them social impact and not just economic impact was an evident and unquestionable way of understanding impact. All of them worked with communities and had been selected to join the programme because their projects are socially connected. The multi-dimensionality of the idea that value is not just economic, but also civic, environmental, and social was already assumed. Some of them tend to privilege the environmental dimension, others tend to see inclusion and participatory issues more, others look into the artistic value, and so on. I think they were naturally having these sensibilities because of their background and experience as almost all of them work in community-based projects and socially-geared artistic work. Also, their personal profile, even if ideologically diverse, is very action-oriented, policy-oriented, and socially committed. Additionally, the initial description of the trajectory itself pointed out the social fabric as essential, and that was assumed by the group from the beginning. The Reshapers started from the idea that artistic work is work to be done within the community and that the value of the art scene stems from work with the community and its resulting impact.

They were also in the understanding that this is the perspective of independent artists, producers, institutions and curators, and so on. Independent here means a scene that draws upon multiple rationales, not just an economic rationale or an audience-oriented rationale, or a cultural mainstream rationale. It is a scene that is open to diversity, including the diversity of processes of work, of relations with communities, and of types of impacts in those communities.

From here, the discussions evolved to address questions about the ‘system’, the broader issues of the structure of the arts system in our contemporary times and especially in the wake of Covid-19. What are the factors of the ecological, economic, and other crises we are living and what are the conditions lived by artists in the wake of these crises? How do they affect what we create? That was the core of the preoccupations of the participants, who were keen to ask how we as artists, creators and organisers of creation can build value in this context? And how are we valued and remunerated? What are our conditions of work in this system? How can the art world change the system?

The discussion extended also to another layer, namely the RESHAPE project itself and how it is designed, and how it is functioning, with questions like how does RESHAPE organise itself and what are the differences in roles and power between Reshapers, facilitators, organisers and partners.

[LA] Within this trajectory, a shift happened from focusing on the value of art in the social fabric to the value of the artist in the social fabric. What is behind this shift?

[PC] I think that, adding to what was said before concerning the perception of the multidimensionality of value, and the relation with social fabric and the work with communities, there was a clear awareness that the group was concerned with the processes, with the ways of doing things, more than with the results of the outputs of those processes. This also led to the focus of interest on the artist, the person, the cultural agent, the social actor, more than on the art itself, or the artwork. I think that the focus was not just on the artist, but in all the roles within the artistic world – artists, cultural producers, curators, cultural managers, institutional leaders, and so on and their positions and roles in the functioning of this art world, as people who were eventually responsible for any changes in its functioning. If there was a clear notion of need for social change, it was somehow natural that this discussion on the value of art in social fabric has moved and focused on the role of the actors that could be responsible for or empowered to effect that social change.

[LA] What were the Reshapers’ background?

[PC] The group was very diverse, in terms of cultural background, professional experience, position in life cycle, territorial origin, and even ideological perspective. We had participants from the South and Southeast of Europe (Spain, Greece, France, Romania, Serbia, Croatia), a participant from Libya living in Europe, and a participant from Britain working in Palestine. While all of them were involved with their surrounding communities, they had different profiles. Some of them were essentially artists and creators, others were more interested in the curating of artistic work and some were essentially cultural managers. So they were quite complementary as a group, although they had different interests and motivations. There were some difficulties in terms of having a concrete common objective in the end, a prototype, but I think that happened in other groups too.

[LA] What was the prototype adopted in your group in the end?

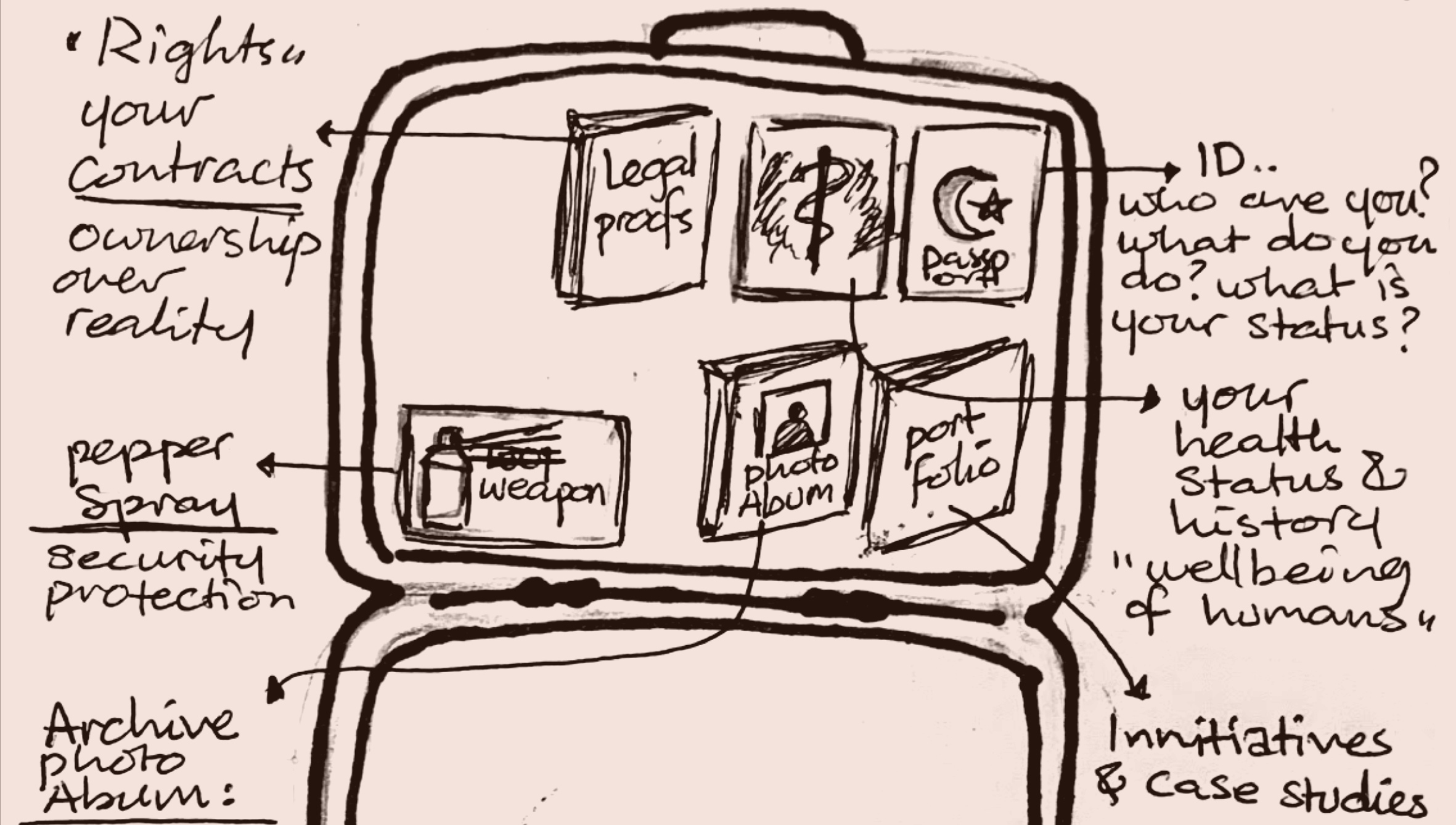

[PC] The home and the suitcase prototype: it is a powerful metaphor on the position of art and artistic world agents, particularly the artists, in the world of today. It was operationalised in the form of a website structure with this theme, combining different things.

The group was first questioning the idea of the prototype as part of their discussion of the RESHAPE project, its setting, its selection criteria, and so on. The idea of a prototype was first viewed with some scepticism. The idea of a result-oriented project also brought out the layer of being independent versus working with partner institutions. From the beginning the group had the idea that what would interest them was the process, the reflection generated, the results of the interconnections, more than the result in the form of an output, a deliverable to the European Union or the project partners for use. Here, many fears, and maybe misconceptions, arose, such as the fear of instrumentalisation, of subversion of their ideas, which in a certain way, brought out their fears as ‘independent’ artists/agents vis-à-vis cultural/economic ‘mainstream’. Of course partners differ, some are big institutions, and some are small. Some are funding institutions and some aren’t. But in the group, some had a sense that a result-oriented project is but a means to test ideas through prototypes that funders can get ideas from. There was this tension that was difficult to resolve. There was a fear that the partners, for example, could not grasp the full richness of the processes they were into, just being concerned with the results and deliverables.

Then our second workshop was in Ghent in February, before the lockdown, and that was the point at which people started identifying more concretely what they wanted to work on. It was first quite dispersed as everyone wanted to follow their own line of thoughts, and their diverse interests. Individually and in small groups, a lot of work was done to explore a diversity of issues within the main framework of the group’s interests. After that, we had the lockdown, so we continued meeting on Zoom, sharing personal experiences with the lockdown, the situation in the various countries, policies that were implemented, and how it was all affecting artists. In our remote Lisbon meeting (a meeting that was supposed to take place physically in Lisbon but the lockdown didn’t allow it), we started building a narrative, understanding the different connections we were bringing, gearing towards a prototype.

The multiple discussions, debates within the group, and exploration of individual work led to a collective awareness of the vulnerability of the artist/cultural agent, particularly the independent artist, producer, curator, and so on, to grow within the group. They brought about an awareness of the challenges artists have to face with regard to multiple crises: economic, environmental, and social crisis, the migration and refugee crises, health issues. The discussions also brought an awareness of the challenges within the functioning of art systems and their institutions, specifically with the position of independent artists; their precarity, their dependency. There was an awareness of the disempowerment in these different dimensions, while at the same time there was an assumption of a rhetoric, even within this project, of the power/role/and importance of independent artists in changing the social fabric.

The project chosen was a metaphor of the home through the suitcase. The idea was to focus on a process and not the result. We had a reflection on the situation of the art world and the system using the home metaphor, home in the sense of the shelter, the space of freedom, the space of dreaming for the cultural sector. When talking about home, there were questions of who owns the home, who can enter, who can’t, who has power to do things within. And then we had the reality of the suitcase that people have to carry, the personal space of survival in this world and in this sector. We thought of refugees and people who have to move from one place to another, with a suitcase that they have to have ready to run with, completely changing their lives.

In the end, the home put forward all the challenges that the art world is facing, at multiple levels and scales, crossing many concepts, questions, and operative tools, envisaging a space of fairness, inclusion, and safety that would enable social change. At the same time, the suitcase embodies the personal space that one has, to survive in this world and to face those challenges. The value of art in the social fabric results from the spaces of possibilities and tensions within this framework.

The idea was to have a website as a tool for the operationalisation of this idea, where we see several links to the various works created in the house. Every part of the house was symbolic of something; the living room, the entry area, the kitchen… It was a metaphorical and symbolic device.

It was important for the group that this wasn’t a finished work, but rather something that could be completed through a constant process of reflection, with the particular visions they have, coming from different realities. It was also important that this device would be open for sharing within the RESHAPE community, where it can be tested and improved.

The process was important for people to be aware of their role and the value of what they were creating in the social fabric.

[LA] To what extent can we say the prototype has reached a finalised stage?

[PC] We can say it is a never-ending work. The group had a difficulty to have a finishing point, or to have an agreement on what should be the level of compromise in order to deliver something like a more or less final prototype, something that, because of its own nature, never will be completed. They were happy with the results they had so far, in the sense that what they were delivering wasn’t meant to be exhaustive. They were happy to have an open end, something that people can relate to, and interact with, and complete in the future.

The group faced the dilemma between delivering a pragmatic toolkit that would not change the world, or their lives, and assuming that the important thing for them was the process of this journey. To share their reflections, with some tools, on how this journey changed, or may change, something in their way of doing things, in the way big art institutions and independent artistic institutions operate, contributing in that way to changing the world on that scale. I would not say the ambition of changing the world was restrained, but instead there was the perception that the small steps for change can only be achieved in the daily work, on a small scale, in the change of individual practices, and for that the sharing of results, practices and tools that is enabled with this prototype has its use, and can be powerful if it affects and changes some of the practices of some partners. The group’s assumption that what is important is the process, more than the results, was, in the end, translated into a result that brings the process to the persons, and that enables to share some of the things they learned with the process itself, be those pragmatic tools, as well as anxieties, philosophical questions, or just provocations.

[LA] There is a way to understand art in the social fabric in terms of how art influences space in direct and indirect ways. By space, I mean both physical space and broader political and social space. Given your expertise in the areas of critical urbanism and planning, did you bring in any of that to the conversation or the thinking towards the prototype?

[PC] I think so. I was participating in the discussions, in some more than in others, especially given that the Reshaper-facilitator relation in the project was constantly evolving. The structural approach I was trying to test with the group in the beginning of this process was related to something that I was working with, namely impact assessment of cultural activities, in terms of the development they bring to the territories/communities. We made an impact assessment exercise in Prague where we met, and where I proposed to them several dimensions, a total of 15, to test what are the perceptions that people have about the impact of their own activities in the community. These dimensions were: economic vitality; economic growth and local prosperity; employment quality; social equity; participants’ fulfilment; local community engagement; participation and citizenry; identity expression; artistic/cultural value; community wellbeing; cultural enrichment; physical integrity; biological diversity; resources efficiency and environmental purity. The discussions involved thinking about the perception of impact, versus the narratives and discourses created in order to attract funding.

But in general, there wasn’t much space for further discussions on this. There was more interest in ideas of changing the world through urgent action. The urgency of action was very marked in the process.

[LA] When you met with the group in Ghent, there was a possibility to do less introspection, and to go out and meet with different cultural spaces with diverse practices. How did these encounters go and what openings did they offer?

[PC] I think these encounters allowed for some openings, even if people didn’t value so much the fact that the programme was very intense during these workshops. There was a concern that there was too much to do, to process, to think and to reflect on the prototype, in full days of a very demanding schedule. Yet people recognised the huge importance of these encounters, not just in Ghent, but also in Prague where they also met.

In Ghent, the Reshapers met with some groups who are doing similar things to what they usually do, which was interesting. In some cases, the encounters brought some critical discussions about the instrumentalisation of communities in some of the projects shown. The Reshapers were not just passively attending these showcases, but were critically engaging with them, and that is in itself a sign of its usefulness, of course.

[LA] What was reshaped for you from the conversations, the suitcase prototype you developed with the Reshapers, the offline and the online encounters?

[PC] There was interesting and important knowledge from the entire process for me to use in my research practice. All the exchanges of knowledge and experiences within the group, all the discussions and debates, were an experience of the utmost importance and value for my activity as a researcher, academic, teacher, and occasional player in this field. We developed nine workshops, each one organised by one of us, and experienced very diverse methodologies for exploring our topic and how to work together, some developed by artists, as well as by people from other backgrounds, and some of these methodologies were quite new and interesting for me.

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.